-

Make the West Great Again – Interview with Angelos Chryssogelos

Podcasts - The European View Podcast

20 Oct 2025

-

A European way of war – Interview with Garvan Walshe

Podcasts - The European View Podcast

03 Oct 2025

-

How Will Trade Shape the Future of Transatlantic Relations?

Multimedia - Other videos

31 May 2022

-

Bridge the Channel May 2022

Bridge the Channel - Multimedia

20 May 2022

-

Bridge the Channel April 2022

Bridge the Channel - Multimedia

14 Apr 2022

-

Trade & Technology Council: Renewing the Transatlantic Partnership

Live-streams - Multimedia

10 Dec 2021

-

The Week in 7 Questions with Nathan Shepura

Multimedia - Other videos

05 Nov 2021

-

[Europe Out Loud] Doom: a chat with Niall Ferguson about the history and politics of catastrophe

Europe out Loud

04 Nov 2021

-

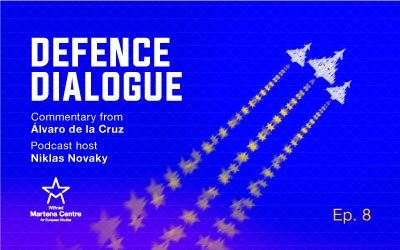

The APEC Summit and the Global Reflection of Pacific Issues

Blog

26 Oct 2021

-

Transatlantic Relations After AUKUS

Blog

21 Oct 2021

-

The Week in 7 Questions with Niklas Nováky

Multimedia - Other videos

01 Oct 2021

-

TTTC: Democracy vs autocracy and the great-power showdown

Live-streams - Multimedia

20 Jul 2021

-

EIF 21 Panel 4 – A Geopolitical European Union: Towards Greater Autonomy?

Live-streams - Multimedia

30 Jun 2021

-

EIF 21 Panel 2 – Europe’s Role in the Great Power Competition

Live-streams - Multimedia

29 Jun 2021

-

Defence Dialogue Episode 12 – The EU’s Quest For Greater Resilience

Defence Dialogues

15 Jun 2021

-

The Week in 7 Questions with Anna-Michelle Asimakopoulou

Multimedia - Other videos

28 May 2021

-

Putting Trade at the Heart of a Global Transatlantic Relationship

Live-streams - Multimedia

26 May 2021

-

Defence Dialogue Episode 8 – A Reboosted Transatlantic Alliance?

Defence Dialogues

03 Feb 2021

-

The Week in 7 Questions with Bruno Maçães

Multimedia - Other videos

29 Jan 2021

-

Defence Dialogue with Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges

Defence Dialogues

25 Apr 2018

Loading...

Loading...