“Oh Kemal, I Have Surpassed Thee!” – Erdoğan’s Folie des Grandeurs

16 July 2020

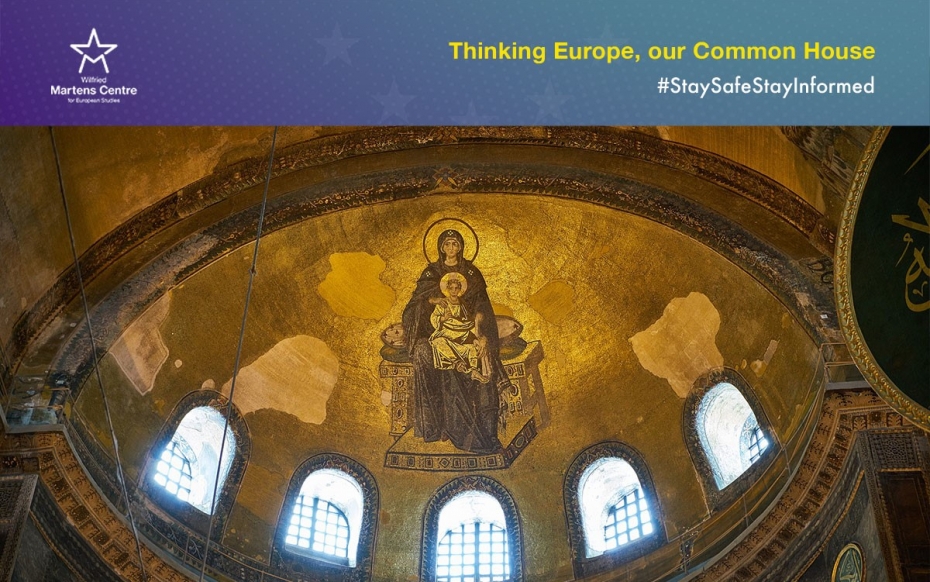

Perhaps there is no better proof of Hagia Sophia’s universality than the array of names it has borne over the centuries. Αγία Σοφία, Sancta Sapient, Ayasofya, were all used to refer to this Christian Basilica dedicated to the Holy Wisdom. It served for 1500 years as a place of worship for Christians and Muslims and, as of a few days ago, as a World Heritage Museum under UNESCO’s patronage.

It is this monument that Turkish president Erdoğan decided to re-convert into a mosque by reversing Kemal Atatürk’s decision from 86 years ago. For Atatürk, the symbolism of turning Hagia Sophia into a museum was clear. After a century of wars and persecution of its religious and ethnic minorities, the Ottoman Empire had been significantly reduced in both size and population. His dream for “peace at home, peace in the world” required neutralising religion as a source of internal division or external threats.

The reopening of Hagia Sophia as a mosque is planned for 24 July, the anniversary of the signing of the Lausanne Treaty in 1923. The Treaty regulated the borders and international commitments of Kemal’s new republic, including respect for both minorities within its borders, and the sovereignty of its neighbours. The symbolism could not be more apparent: Erdoğan sees this treaty as an obstacle to his ideological and strategic revisionism. The geopolitical implications of the Hagia Sophia decision are clear.

This decision goes beyond Turkey’s relationship with Greece, a country that has, for obvious reasons, taken the decision as an affront. It also goes beyond Europe and the West as a whole, as Erdoğan’s objective is to keep his domestic base mobilised. This move undermines global norms, rules, and efforts of inter-civilisational dialogue. The casualty of this decision may end up being nothing less than peace and understanding on a global scale, undermining relations between the West and Islam as a whole.

Turkish officials claim that Hagia Sophia is a purely internal matter. However, it is hard to see how the international community can ignore the emergence of radical civilisational discourses in Turkey, like the statement of AKP Party’s deputy chairman, Numan Kurtulmus, that “[…] those who conquered It by the sword also own the property rights”. Such statements are unworthy of a country privileged to host myriad World Heritage monuments, which, however, also come with international responsibility. All states hosting UNESCO sites are repositories of humanity’s shared history and universal values. Consequently, they are accountable for how they treat this global patrimony.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the Hagia Sophia decision comes at a very delicate political time for Erdoğan. The recent local elections in Turkey, the collapsing economy, and the mismanagement of the COVID-19 crisis have created unrest in Turkey that the AKP government cannot handle. As is typical for populist and authoritarian regimes, the remedy for the inability to deal with citizens’ actual problems is a turn to nationalism and religious fanaticism.

The decision was preceded by a publicity campaign to create the impression that the Turkish population is supportive. But in a recent survey by Istanbul Economics Research, Turks appeared divided: 47% were in favour, while 38% were against. Additionally, many Turkish scholars and politicians (Orhan Pamuk, Ahmet Davutoglu, and Ekrem Imamoglu, among many) called it a terrible mistake. Much as everything else Erdoğan does these days, this decision just serves to divide Turkish society, solidifying his base while targeting his opponents. Contrary to how Erdoğan tries to present it, opposing Hagia Sophia’s reconversion into a mosque does not equate to ‘opposing Turkey’: it means standing up to a regime which an increasing number of Turks are growing hostile towards.

Erdoğan is on a frontal attack against all values of the West’s past and present, from secular ideas of democratic liberalism to its Christian heritage. When geopolitical reorientation becomes embedded in a language of cultural inconsistency, it is difficult to see how there is any way back. A move that signals such blatant disregard for Turkey’s international commitments, even in the cultural field, can only portend further brinkmanship in the political and strategic field. Europe must be under no illusion. Turkey is an important partner. But you can only be a partner with someone who also sees you as one. If the EU wants Turkey to return to the table as a reasonable interlocutor (under the current government, or another one), the EU must prove it is a serious actor in its own right against Erdoğan’s provocations.

The Hagia Sophia decision is part of a long series of hostile acts against Europe by a regime degenerating into a rogue actor. The EU has more than sufficient justification to impose targeted, proportionate, but, if necessary, escalating sanctions in a variety of fields – economic, touristic, military – on Erdoğan. This is not meant as a punishment against the Turkish people, or to rupture the EU’s ties with Turkey terminally. There is simply no justification to indulge a regime that engages in such blatant authoritarianism at home, and aggressive revisionism internationally. A firm stance against Erdoğan is in the interest of both democracy in Turkey, and stability in the region.

Finally, a note about EU foreign policy more generally: Hagia Sophia has highlighted the importance of cultural heritage, particularly in the Mediterranean and the Middle East, as a topic of international diplomacy. Cultural heritage beyond the EU’s borders is a legitimate concern. The EU has long been absent in this area, at a time when wars have taken a horrible toll on cultural and religious diversity in its strategic periphery in the Middle East and the Mediterranean. A ‘strategic Europe’ must also be one that is ready to defend culture, civilisation, and diversity, not only at home, but abroad as well.

Credits: Photo by Engin_Akyurt on Pixabay

ENJOYING THIS CONTENT?