App Wars: The EU Must Prepare for the Digital Skirmish

25 March 2021

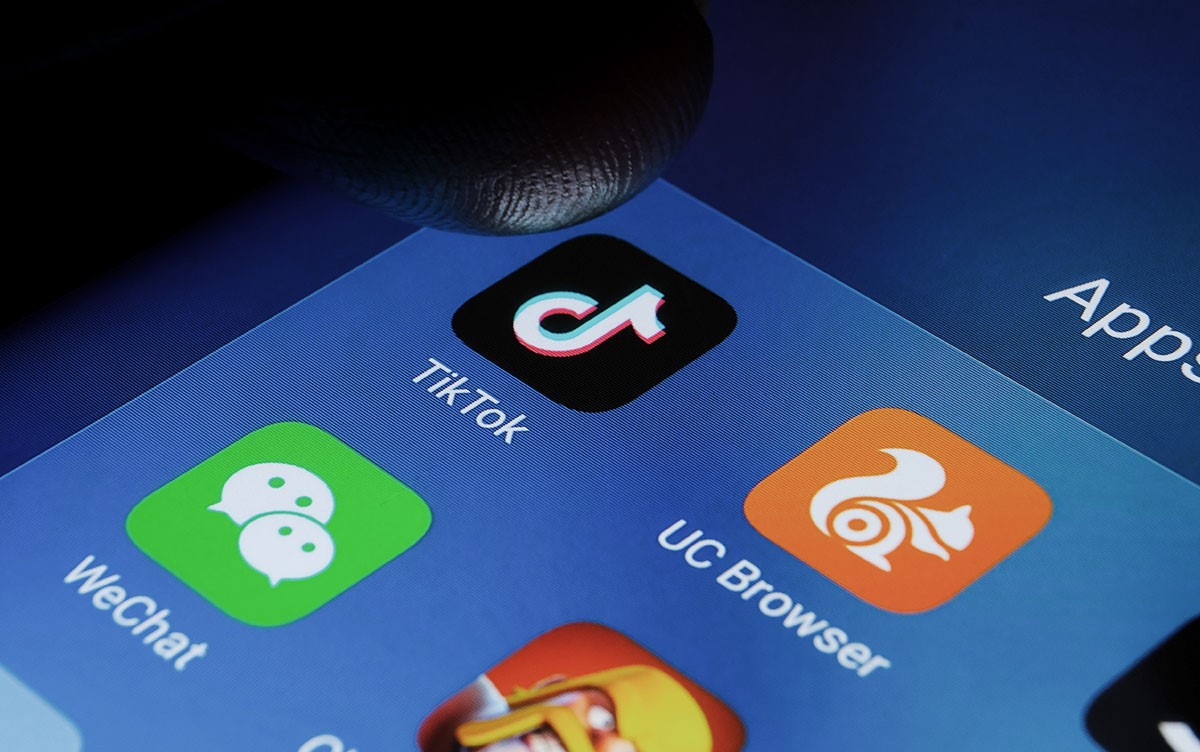

In mid-2020, a lethal clash occurred between Indian and Chinese troops in the border region of Ladakh. Soon after, India opened fire on the digital front by banning dozens of Chinese mobile applications and declaring them harmful to Indian sovereignty and security. In a similar fashion, the US digital hawk brought its gaze on a technological prey. On national security grounds, the Trump administration initiated a crusade against the likes of TikTok, WeChat and Alipay.

The US’ handling of the TikTok saga has been a messy affair, with the new presidential administration appearing to backtrack on the ban. There are legitimate concerns that foreign businesses shouldn’t be in the crosshairs of politicians, nor should users be collateral damage in the technological rivalry between the US and China.

The national security rationale applied by India and the US in this digital skirmish might appear overblown, but there is an important case to be made. How should our governments respond to online businesses acting in a nefarious way? How should our institutions treat digital platforms which can be conduits for authoritarian influence?

Let’s quickly look under the hood of two of the most popular Chinese platforms. The ‘super-app’ WeChat offers a bundle of services, with more than a billion active users and around 100 million downloads outside of China. WeChat is not only heavily surveilled within China, but also monitored abroad, with strong political censorship of user conversations. The Chinese Communist Party has been using this platform to target the Chinese diaspora in other countries, apply information control, and spread disinformation.

International superstar TikTok also favours content moderation and applies censorship to politically sensitive topics. Both WeChat and TikTok have been embroiled in controversies about the storage and transfer of personal data. Don’t forget that these businesses have to comply with draconian Chinese legislation that requires companies to support national intelligence work.

Some readers might consider such alarm about cute videos or chat platforms a bit premature. But this is just the tip of the iceberg and the problem is not limited to apps. Cheap Chinese Internet of Things (IoT) devices are quickly expanding their share of European markets where standards for such technology are still wobbly. Interconnected home speakers or smart devices remain extremely vulnerable to cybersecurity breaches and are likely to leak user data. It is a matter of time before Chinese AI-driven hardware and software starts raising serious ethical, cybersecurity, and espionage concerns.

The EU must develop stringent standards for the access of advanced digital hardware and software from third countries.

While all of this unfolds, the European dove sits and waits. Much of the EU’s recent efforts have been aimed at Silicon Valley companies and their dirty business when it comes to monopolistic behaviour, monetisation of personal data, and stifling competition. This is a laudable effort but the EU should not underestimate the threats coming from the digital juggernauts to the East. European commitment to online privacy should not be our only line of defence against the ongoing onslaught from China. This is no longer solely a question about bureaucratic personal data management, it’s a question of national security.

The EU must develop stringent standards for the access of advanced digital hardware and software from third countries. The same way we have common rules for consumer goods safety or health requirements for imported foods. The same way we blocked the entry of cheaper Chinese cars which didn`t cover European safety requirements a decade ago.

This should come in parallel with other comprehensive measures to boost our defensive digital capabilities in cyber security and the protection of critical infrastructure, not to mention the need to decisively boost our export controls on selling advanced technology to countries with appalling human rights records. The EU has imposed an arms embargo on China since 1989, but why are we still supplying them with surveillance and dual-use technologies?

Our commitment to free trade and global supply chains don’t mean that we provide unconditional access to our markets and networks. It is unnerving that we are debating whether it’s fair to scrutinise the market access of Chinese digital platforms, while Beijing unscrupulously maintains a wide-ranging ban on hundreds of US and European apps and digital services. In a similar act of techno-nationalism, Russia is trying to limit the exposure of its population to Western digital platforms by obligating phone providers to pre-load all new smartphones with specific Russian-made social networks, payment apps, and voice assistants.

There is the optimistic tale that the Internet will always remain open and that international actors will inevitably embrace the digital domain as a tool for empowerment and joint cooperation. This belief is as noble as it is erroneous. The global system of Internet governance resembles the characteristics of the ‘analogue’ international system – ruthlessly competitive, and prone to regionalisation and conflict. We must finally acknowledge that the likes of China and Russia are not benign actors – Europe is dealing with aggressive authoritarian regimes both online and offline.

The US President Theodore Roosevelt liked to recite the West African proverb: ‘Speak softly and carry a big stick’. On the digital front, Europe speaks softly but often comes empty-handed.

This needs to change.

ENJOYING THIS CONTENT?